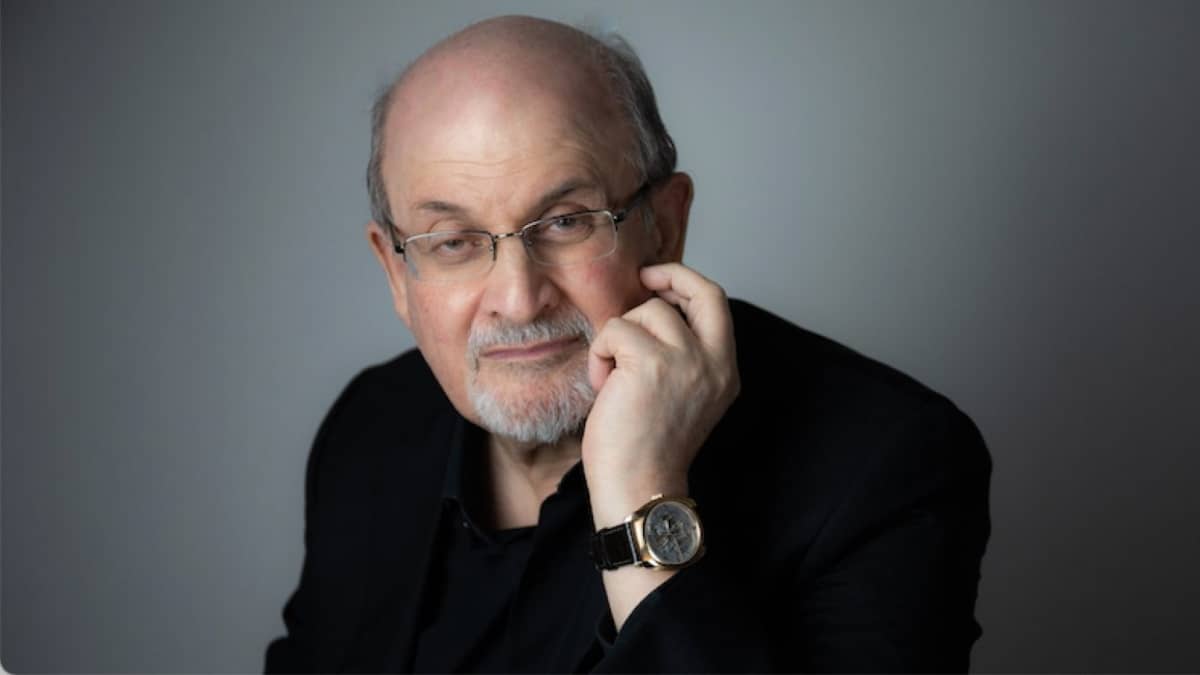

Last week when I heard that the international best-selling author Salman Rushdie had been stabbed in Western New York shortly after signing up to support writers living in mortal peril, it was the timing rather than the event that came as a surprise, if only for my acute appreciation of irony.

The Indian-born British American novelist enjoyed success eliciting only a modicum of controversy after the publication of his first three novels. It would be his fourth, and perhaps also the book for which Rushdie is best known, The Satanic Verses, that would ultimately be the reason the author would spend the next nine years of his life under police protection.

In the novel, what offensive and unforgivable transgression might Rushdie have included that the Iranian dictator and despot Ayatollah Khomeini would issue a religious decree, or fatwa, insisting the author and his publishers be murdered?

Blasphemy.

To the moderate person of any faith, blasphemy seems hardly a valid reason to issue a religious command that insists someone pay with their life. Only a fanatic of the worst degree, and in the Ayatollah Khomeini’s case someone of ill repute, would think that death carried out in its cruelest form can atone for blasphemy and what he also called an abuse of free speech.

In 1988, the year preceding the fatwa on Rushdie’s life, Muslims around the world took to the streets in protest of The Satanic Verses. Demonstrations persisted and, in some parts of the world, turned violent. As global pressure from Muslim communities mounted, in an attempt to show solidarity – or perhaps out of fear of reprisals for not standing with the offended Muslims – various countries decided to ban the sale of the book. South Africa, my country of birth, was among the many states that took the decision to prohibit the dissemination of the publication. Apartheid, meanwhile, was an absolutely egregious human rights catastrophe to which the filthy National Party clung in spite of international pressure in earlier years. Prioritising was not the Nats’ strong point, clearly.

Early in 1989 came the moment when Salman Rushdie would realise, perhaps for the very first time, the amount of trouble in which he and his publishers had landed themselves. The following message was broadcast on 14 February of that year by the Ayatollah Khomeini on Iranian Radio.

“We are from Allah and to Allah we shall return. I am informing all brave Muslims of the world that the author of The Satanic Verses, a text written, edited, and published against Islam, the Prophet of Islam, and the Qur’an, along with all the editors and publishers aware of its contents, are condemned to death. I call on all valiant Muslims wherever they may be in the world to kill them without delay, so that no one will dare insult the sacred beliefs of Muslims henceforth. And whoever is killed in this cause will be a martyr, Allah willing. Meanwhile, if someone has access to the author of the book but is incapable of carrying out the execution, he should inform the people so that [Rushdie] is punished for his actions.”

Since the attack last weekend in which Rushdie was stabbed ten times, including in the liver, neck and in the eye, there has been a deluge of news articles detailing the assault and referring to the attacker only as a “24 year old man”. It has now been established that while the assailant Hadi Matar is not himself directly affiliated with any Islamic extremist group, in a recent Facebook post he did show solidarity with Hezbollah and it is now thought that he, too, was “motivated by Iran’s longstanding fatwa”. Fear of violent pushbacks, I can imagine, is the only reason CNN and other large news organisations failed to link Rushdie’s attacker to radical faith groups. It is also for this reason, I believe, that these same news organisations failed to display the cartoon images that turned the offices of the Danish newspaper and the French satirical publication Charlie Hebdo into a bloodbath.

Of the many condemnations that can be made about Iran, inconsistency is not one of them. Following the attack on the author last Friday Iran has denied any direct connection to the incident, but did go on to say that it does not commiserate with Rushdie and that he got what he deserved. Let it not be thought for a moment that those sympathising with Iran and other radicalised extremist groups are to be levelled with, or that rational debate can be had with them. We are, after all, talking about a fictional novel that Rushdie published.

I would be remiss for omitting in this piece that not all Muslims are fundamentalists who live to spill blood and cannot wait to blow themselves up and, thereby, attain martyrdom. Only a callous person who is as unreasonable as the fanatics against whom I speak out would think all people of that faith are equally wicked.

The 1989 fatwa issued against Salman Rushdie was to serve two purposes. First, it was meant as a punishment for the abuse of free speech and more to the point, for blasphemy; a sin, if you will, that can only be accounted for by death, according to religious scripture and adopted by those radicals on the fringe. The second reason, it seems only logical to me, was to inculcate into publishers and booksellers a fear of the kind that would see The Satanic Verses pulled from the shelves and also dissuade other publishers considering material that might stir up belligerent faith-based groups. However, since the stabbing last weekend, The Satanic Verses has soared to the top of the book charts once again showing that the pen is still and always will be mightier than the sword.